Paradoxical Joy: stigma and coming out as the mother of an incarcerated person.

Month: October 2014

Paradoxical Joy: stigma and coming out as the mother of an incarcerated person

Our simultaneously freedom- and control-obsessed society stigmatises prisoners, former prisoners, children of prisoners, siblings of prisoners, and parents of prisoners, much as it stigmatises people who use drugs and sex workers, particularly if they are poor and non-white. My oldest son is biracial:Caucasian/Salvadoran, tattooed from head to toe and, growing up in Northern New Mexico, always identified as Chicano. As a youngster he was in and out of juvie, has been homeless in New York City and Albuquerque, and no matter how many treatment programs, counselors, and twelve step groups he has attended, has been unable to stay sober for more than 18 months at a time.

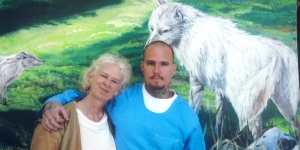

When he relapses, Pablo blacks out and commits non-violent misdemeanours that a California judge finally rolled into a felony charge, a “strike”, sending him away for a three year bid at a maximum security prison. He lives in a “dorm” rather than a cell, with hundreds of other men, including many lifers, one of whom is now his “accountability buddy” in a prison twelve-step program. When I visited him the other day he was sober, clean, and very clear about his spiritual freedom. We had a wonderful five-hour visit.

As the mother of an incarcerated son, I have the choice to either accept the stigma, the shame society projects on me by never to talking about this “status”, or can reject it by speaking the truth aloud when appropriate. I don’t beat people over the head with it, or bring it up out of context. Neither do I avoid it if the subject of where my children live or what they do, comes up in conversation.

When I do mention that my son is in prison, most people respond with shock and embarrassment, much as they do to announcements about terminal disease or death. “Oh I am so sorry” said the African American Enterprise shuttle bus driver as he took me, his only passenger, to my rental car at LAX at 5am. He was making polite conversation about my destination once I picked up the car, and when I said I was going to Tehachapi, to visit my son who is in prison there, he predictably expressed dismay. Yet we ended up having a wonderful conversation, as he recalled how energised he and his uncle would be when he visited the nursing home where his relative was confined following a series of strokes.

Although the US has more than 6 million people under “correctional supervision”, a number comparable to imprisonment rates in Stalin’s gulags, people who don’t know, or don’t have an incarcerated loved one, are still shocked that an ordinary looking middle class, middle-aged white mom such as myself should have a son in prison. The multi-billion dollar “corrections industry” functions in a parallel universe from the comfortable lives of most Americans. It is, however, the universe of many lower income African-Americans, Native Americans, or Hispanics from certain neighbourhoods and states, and often I am the only white person in the visiting line, surrounded by women and children of African and Hispanic descent. Prison temporarily effaces the privileges of whiteness.

“Coming out” as the mother of an incarcerated person means telling people how much I love visiting jails and prisons to see my beloved oldest son. Which does not, of course, mean that I think he, or many of the other men we interact with during visits, belong inside. I love it because I get to feel and share in the joy and anticipation among the women and children in the waiting rooms, in the lines we have to form to get into jail, and in the shuttle bus to the yards. There is a palpable sense of community, family, sharing, friendliness, and the relief being about to see our loved ones after a long separation. Shame and stigma have no place in our interactions. We are all there because we love our prisoners. We are not strangers to one another.

Yesterday, when I was meditating on it, I realised that the joy and anticipation I experience in visiting a jail or prison to see Pablo, resembles the joy and anticipation of Advent. We are all waiting to see, hold, and speak with our loved ones, something that happens only rarely for most of us. And we anticipate their joy at seeing us, at feeling the first hug, drinking in each others’ presence for a limited time, and telling all the news and truths we can squeeze into those brief hours before the call “Visit’s over”. There is a quality of appreciation in the encounters that is lacking in most of our encounters in the outside world, a quality that reminds me of the how I used to feel as a hospice volunteer, being with people during the final stages of their lives. Our precious time together is distilled into the very few things that really matter. The value of our moments together is magnified in a way that our non-prison encounters, sadly, are not.

The central dynamic of both terminal illness and incarceration is, of course, loss of control, or rather loss of the illusion of control, and yet it is almost a cliche to say that many people who are dying, and some, like Pablo, who are locked up, sense an inner freedom that was previously inaccessible to them. The freedom of not being in control is a source of joy. Another paradox of the power of love, which relegates the power of the state to the shadows.